Offshore wind and the Atlantic Loop

Larry Hughes

2 August 2023

In a year's time, North America's largest offshore windfarm, Vineyard Wind 1, is expected to be completed.

The 800-megawatt windfarm will consist of sixty-two 13 megawatt turbines located about 24 kilometers south of Martha's Vineyard in the Atlantic Ocean.

Each turbine's tower is expected to be about 260 meters tall, with blades 220 meters long.

To get an idea of the size of these turbines, take a walk along Halifax's waterfront. In the harbour, there are ships laden with monopile foundations waiting to be assembled for installation to support the turbines, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: GPO Grace in Halifax Harbour with turbine foundations

When fully operational, Vineyard Wind 1's turbines will generate about four terawatt-hours of electricity a year.

The Nova Scotia government has legislation to open the province's Atlantic coast for about 5,000-megawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030.

If the province's target is reached, the offshore could generate more than twice the volume Nova Scotia Power produced in 2022.

According to the province's offshore wind website, "Offshore wind can help reduce fossil fuel use and help Nova Scotia meet the province's climate change goals".

Ideally, the volume of electricity produced by these, and other, renewables will let Nova Scotia and the new industries producing green ammonia meet their clean energy requirements.

However, variable renewables like wind are just that, variable. There will be times when the supply exceeds the demand and others when the supply falls short.

The question is, what will we do when production exceeds our demand or falls short of what we need?

One answer is to have a reliable supply of electricity that "follows" the variable supply, meeting the shortfalls when required.

This is why the eastern part of the Atlantic Loop from Muskrat Falls to Nova Scotia is important. It will allow Nova Scotia Power to increase the capacity of renewables on the grid.

However, the eastern Atlantic Loop alone will not let the province reach its 2030 climate change goal.

What could be used?

The most obvious choice is the western part of the Atlantic Loop, first proposed by the federal Liberal party in 2019 election.

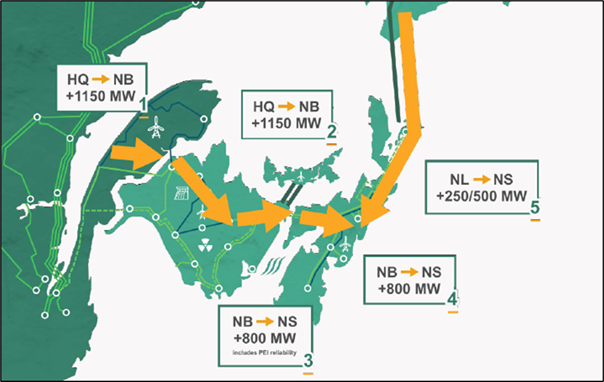

However, as late as 2022, the western Atlantic Loop was vaguely defined, as the map in Figure 2 from the final report of the Clean Power Roadmap For Atlantic Canada shows.

Figure 2: Routes and capacities for eastern and western parts of the Atlantic Loop

In this route, electricity from Hydro Québec is to pass through the Gaspé into northern New Brunswick, and then south and east to Nova Scotia.

However, Nova Scotia's premier is dead set against the Atlantic Loop, claiming it could bankrupt the province.

The province claims that more variable renewables plus storage will suffice to meet the 2030 climate target.

Maybe, but we should be considering alternatives because if offshore wind exceeds the province's demand, there will be more electricity than the province needs.

Interestingly enough, Québec will need an additional 25 terawatt-hours and 100 terawatt-hours of new electricity by 2032 and 2050, respectively.

If the western Atlantic Loop was available, Nova Scotia could trade electricity with Québec.

Fortunately, there are alternatives to the route through New Brunswick. A student of mine is examining the possibility of connecting Point Aconi in Cape Breton with Havre Saint Pierre on the north shore of Québec via submarine power cables.

This would give access to Hydro Québec's grid and its La Romaine 1.5 GW hydroelectric complex.

Nova Scotians need to know where our energy will come from if we are to meet our 2030 climate change goals.

Vague assurances from both the federal and provincial governments are not enough.

A Nova Scotia energy strategy would be a good first step.

Published: allnovascotia.com 3 August 2023