Last month, I did something quite amazing - I traveled from Halifax to Winnipeg, a distance of about 2,600 kilometres, in less than five hours.

Why is this amazing?

150 years ago, before the Intercolonial Railway connected Halifax to Montreal and the Canadian Pacific Railway linked Montreal to Winnipeg, it would have taken several months to make the journey by foot, boat, horse, or carriage. When the railway was finally completed in the late nineteenth century, the trip could be made in about four days. Today, the trip can take less than five hours by jet aircraft.

So to what do we attribute this incredible advancement in transportation? The most obvious answer is the technological transition from steam locomotive to the jet engine between the 1840s and the 1940s.

There is another reason for this rapid evolution: energy. About 150 years ago, when steam locomotives were powered by wood and coal, the lifeblood of modern transportation was discovered in Pennsylvania and around the Caspian Sea: the commercial extraction of oil had started.

Initially oil, as kerosene, was used for lighting; however, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, a new use for oil was found - transportation: automobiles, powered by the internal combustion engine, began to displace horses.

From this point onwards, the technological changes driven by oil progressed rapidly, with the development of the diesel engine, for trains and trucks, and the advent of the jet engine late in the Second World War, for powering aircraft. Gradually our modern transportation system took shape: the automobile for personal transportation, the transport truck for moving goods, and commercial aircraft for moving people and goods over long distances.

Although transportation technology has undergone tremendous changes, the energy that powers it is still a structure of carbon and hydrogen atoms called crude oil.

Before crude oil can be used as gasoline, or diesel, or aviation fuel, it must be refined. Not all crude oil is the same: it ranges from conventional light, sweet through heavy, sour crudes to the unconventional, such as the bitumen found in Alberta's tar sands. The light, sweet crudes are most desirable, as they require very little refining to make gasoline-like products. On the other hand, the heavy, sour crudes need a great deal of refining to, amongst other things, remove sulphur compounds (the sour in heavy, sour). Most of our transportation technology is based upon petroleum products refined from cheap, light, sweet crude.

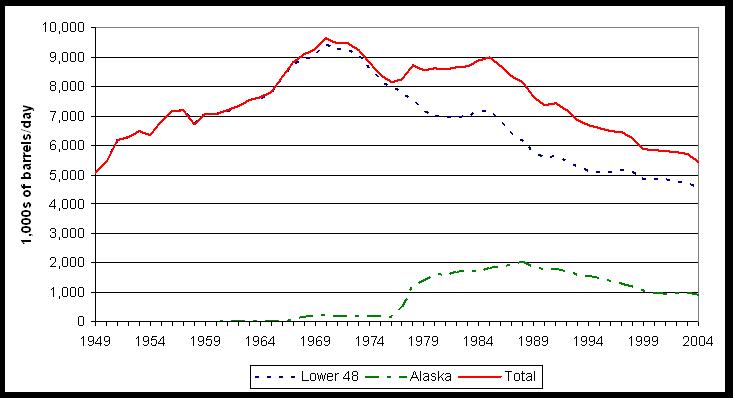

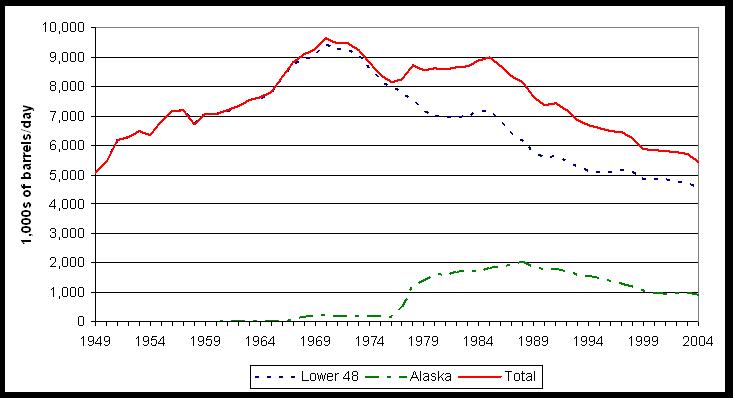

With ever increasing demand, the volume of crude oil on the planet is disappearing; for example, the volume of crude oil produced in the United States peaked in 1970 and has been declining steadily ever since, as shown in the following figure based upon data from the United State's Energy Information Agency:

As individual, then national, oil fields peak and decline, other sources of crude oil must be found. This can be carried out in a number of different ways: between the 1940s and the 1960s, it was through exploration and the discovery of new fields.

Since the 1970s, the size and number of the fields discovered has been declining rapidly, causing petroleum engineers to develop new technologies to remove more of the oil from existing fields. Generally, once a field has peaked, it is next to impossible to stop the decline. For example, over the past thirty years, vast sums of money have been spent on enhanced oil recovery techniques to extract more oil from wells across the United States; the result, as the above figure shows, has not stopped the decline.

The past decade has seen a reduction in the volume of light, sweet crude available for refining. Refineries designed to handle light crudes are unable to process heavier crudes, meaning that either more refining is required or new refineries must be built. Not surprisingly, the cost of refined products increases with the rise in the amount of refining.

Adding to the twin problems of the decline in the number of net producing countries and the rising cost of refining, is the rise in demand for oil products from a growing number of countries. It should not come as a surprise therefore that the price of petroleum products is increasing.

Some pundits argue that today's high prices are a temporary phenomenon as new technologies will both reduce energy demand and find new energy sources. There is some truth in this; for example, some of the new Airbus aircraft get better passenger mileage than does the average North American automobile. However, when it comes to transportation fuels, it is hard to beat light, sweet crude as a feedstock. The same pundits point to technologies being developed to convert grains, biomass, and oil shale into oil-like products, overlooking the fact that the less something looks like oil, the more energy (and money) it takes to transform it.

Perhaps I'm jumping the gun by looking upon my 2,600 kilometre trip to Winnipeg as something amazing - today's technology and energy costs make it seem mundane. As energy prices continue to rise, it's a safe bet that in a few years, many more people will consider a five hour trip to Winnipeg pretty amazing.